This page has a “Short Bio” and a rather lengthy mini-memoir describing my year with SNCC doing voter registration beginning with the 1964 Freedom Summer in Mississippi.

Short Bio

I grew up in Alaska. Part of that time we lived 20 miles from the nearest road, went to school by dogsled, and suffered with outdoor toilets (imagine twenty below and having to go in the middle of the night!). I had mountains, lakes, and wilderness as a playground and even as a young boy frequently went on solitary hunting trips. My friends and I damned up creeks and built a cabin on the mountain-side before I was old enough to be interested in girls.

Even today, after fifty years of living in cities, there is a part of me that still thinks (rather romantically and unrealistically) that I am a mountain man.

At age 16 we moved to Penn State University and I saw my first TV, telephone, and elevator. Over the next few years, both parents, an uncle, and three siblings all attended Penn State while I started an academic journey that took me through separate degrees in science, politics, and management. As all these fields might suggest, I had some trouble deciding what I wanted to be when I grew up.

In 1964, in the middle of my undergraduate work, I joined almost a thousand other Northern students as part of the Mississippi Freedom Summer assault on the segregated South. I stayed in Mississippi until April of 1965 and during that time was attacked by both civilians and a policeman, was threatened by a couple of mobs and by a man with a rifle, and was arrested. God must have been watching me pretty closely, because although I thought I was about to be killed several times, I was never even injured.

My “career” has taken me through a dizzying array of different roles including custom manufacturing, community development, university teaching & research, software development, carpentry, and (since retirement in 2006) writing, both fiction and essays. For a long time, this odyssey through all these careers puzzled me, but I recently realized that all of it was God’s way of preparing me for writing fiction which explores the uses of strategic nonviolence.

Now, in retirement, I am busier than ever. I am part of a group puzzling over the question of how to redesign government to be an effective democracy … or maybe the question is how to develop an operating system for planet earth. I am part of a healing prayer ministry, I tend my vegetable garden, and I continue to try to get my city-bred wife to love the wilderness (“No, Sweetheart, the bears won’t get you and there are no snakes in Alaska!”)

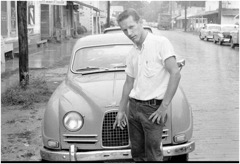

Mississippi Freedom Summer: An autobiographical fragment

I enter hostile territory early afternoon of June 24, 1964. There are about four hundred of us, traveling independently in private cars and we are the second wave of invaders. We are mostly white, mostly well-to-do college kids and we are invading Mississippi, intent on ending segregation. Three young men named Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman were part of the first wave a week earlier and they disappeared three days ago. No one knows but we assume they’re dead. Months later the truth comes out – the Klan and some folks in the local sheriff’s office in the little town of Philadelphia, Mississippi killed them.

We expect to meet violence and, frankly, most of us are scared. We had a week of training to prepare. Fannie Lou Hamer and Bob Moses and John Lewis and many others were our trainers. These folks were battle-scarred veterans of nonviolent civil rights actions all over the South. Most of them had been jailed and one of them, Travis by name, told of being followed in his car and then shot through the neck. Fannie Lou told of being arrested, being beaten, being thrown out of her house. So much courage — we wonder if we can match up.

One of the stories that siezes my imagination involved an indoor segregated swimming pool. The demonstrators, including a long-time Quaker activist named Charley, went into the pool area and everybody but Charley immediately got in the pool. Suddenly the door flew open and a group of white men with clubs rushed in. They ran at Charley, with clubs raised to strike him. Charley never moved except to extend his right hand in the classic gesture for shaking hands. The leader of the mob skidded to a stop, shifted the club to his left hand and extended his right hand to shake Charley’s hand. The rest of the mob skidded to a stop behind the leader and Charley just kept shaking the leaders hand and started talking. There was no violence that day.

I get several lessons from this story. The first is that we react out of habit and the leader of the mob was probably surprised to find himself shaking hands with a guy he planned to bash. The second lesson is that once you engage in a civilized ritual with someone (e.g., shake hands, light their cigarette, give them a glass of water), then it is pretty hard to attack them. The third lesson is that nonviolence takes a lot of guts. The guy might have ignored Charley’s extended hand and broken his skull.

I drive directly to Hattiesburg, in South central Mississippi, an area that has seen quite a bit of violence against civil rights workers. The next morning I am in the office when one of the other new guys comes racing in and excitedly tells me my car has been shot. Half of my distributor cap is gone and there’s a hole in the intake manifold. Two of our cars had been shot in the middle of the night. “Foreign” license plates. Welcome to Mississippi.

I go to the nearest hardware store and buy five pounds of nails. My nails are roofing nails, they are only an inch and a half long and have a head almost the size of a dime. I divide them into two equal piles and put each pile in a paper sandwich bag and wrap a little masking tape around each of them. I figure if someone chases my car, I can throw one of these packages out the window and the paper bag will break, the nails will scatter all over the road and hopefully my pursuer will have a flat tire or two. I’m not really sure this will work, but it makes me feel better and I carry these two packages of nails in my car the entire time I am in Mississippi. Gandhi would not approve of the potential property destruction, but I’m not up to his standards.

o o o o o o o

I am assigned to work in Biloxi, on the gulf coast and a tourist town. All told our project has about 40 northern college kids, most of whom are white, and a half dozen local blacks, most of whom are around 16 to 18. Roughly half of our staff works in the Freedom Summer School and the other half works on voter registration. Sort of by default, I am in charge of the voter registration effort.

The local blacks are mostly afraid. They know too much about the Klan.

The amazing thing is that there are so many blacks who decide to stand up against this system. All forty five of us are staying with local families, for free. Leo’s restaurant is giving all of us half-price meals – and he keeps this up for the entire summer. Several churches enthusiastically support us. But the majority of local blacks are afraid. And this makes the canvassing rather discouraging. The usual response is polite but as non-committal as possible. Between the Mississippi heat and the mostly timid responses, it was hard to keep walking the streets knocking on doors all day long.

My summer passes in a blur of record keeping that often occupies me late into the evening. There are three bars in the black section of town that aren’t total dives and two of them give us discounts on drinks. One of them has a dance floor and a good juke box and it becomes our preferred hangout after work. Even though I don’t really like bars and am a lousy dancer, it’s where all my colleagues are and a couple of drinks really does help relieve the tension. I yearn and lust after some of the girls, but the combination of my shyness and being overwhelmingly busy keeps me mostly alone.

We go the entire summer with no serious violence or trouble with the police, unlike a lot of the other localities. In August, all over the state, all but a handful of the northern volunteers go home. The Freedom Schools close and the kids go back to their regular, segregated schools. Chaney, Schwermer and Goodman are still missing and presumed dead. Most of the media disappear. After the intense work of the summer, we go through a period of weeks where we don’t really know what to do with ourselves. For a while I am the only white on our project.

During the summer, with all the Northern volunteers we didn’t really lack for money. Now, with only a handful of Northern volunteers left in the state, the money dries up. And the local people who have been feeding us all summer are feeling the pinch. Some days we don’t know where our next meal will come from.

I am the only one in Mississippi from Penn State University or even that region. The Penn State regional media, newspapers and radio, have been all over me all summer. Now I discover my mother is a media genius. She has been quietly orchestrating this media blitz all summer and now steps in to help us with the funding. We play the “local boy in harms way in Mississippi” to the hilt and the media enthusiastically helps. I am constantly in the Penn State newspaper, the local town newspaper, and on one of the radio stations. The Penn State area financially supports our entire project all fall and on into the spring.

Only much later do I learn about the death threats my parents are receiving. Penn State and its immediate vicinity are supportive, but the rural areas surrounding the region are full of serious racists and they don’t like what they are hearing about the Clemsons. My folks get nasty phone calls in the middle of the night and threatening letters made by cutting individual letters out of magazines. The folks don’t bother telling me any of this and I don’t learn about it until a couple years later.

o o o o o o o

In early fall, the decision is made to challenge the regular Mississippi delegation to the National Democratic Convention. We get a fresh influx of northern volunteers and go to work, feverishly registering people for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic party. For this effort, it is important to get representation from all over Mississippi – and this means venturing outside of Biloxi, out into rural Mississippi.

I’m not too happy about venturing into the Mississippi back woods and most of our local people flatly refuse to go unless they can take their guns with them. I tell them we can’t take guns and they say “No guns? No way!”

We plan these trips like military campaigns. We look for local people who know these towns and work with them to make detailed maps. Wiggins is a town with a reputation for Klan violence where most blacks live in houses owned by the plantations they work for. A local guy who grew up in Wiggins makes us a great map and, using it, we come into Wiggins on back roads that bring us directly into the black part of town. I drive one of the two cars and I park at an intersection where I can see anyone approaching on either of the intersecting roads. Our fairly pathetic plan (but the best we can devise) is that when I see a pickup approaching, I blow the horn and my four canvassers instantly stop whatever they are doing and come to the car as quickly as possible so we can attempt to flee. God watches over us and we spend more than half a day in Wiggins and see only a couple of pickups and none of them pay any attention to us. We sneak out of town by the same back road we came in on and are deliriously happy to be out of Wiggins without any casualties.

A few days later we are again headed for a small town in the middle of nowhere, with me and three young black canvasssers. We’re about a half-hour from Biloxi, going along a narrow road with forest on both sides and the car starts to overheat. I think we have to stop or burn up the engine so I pull over when I see the small café. Benny, a local Mississippi kid who was my roommate all summer and who fights with me about everything, immediately objects, “This is no place to stop – we need to get the hell out of here.”

I don’t understand. “Why – what’s wrong with it?’

Benny says “Look at it. The place is run down and half of it is the guy’s house. It’s mid-day and it’s not even open – the guy is probably mad at the world because his restaurant is failing. It’s some ignorant cracker, probably a big shot in the local Klan. Come on, we need to get out of here, NOW.”

Benny convinces me – but the car won’t start. We sit there and debate our options and can’t find any that we like. Finally, seeing no other path, I decide to go ask for some water for the car. I ask George for a cigarette which I stick behind my ear and I go up and knock on the door to the house.

No answer.

I knock again, a little harder this time.

Finally the door flies open. An old man literally jumps through the door and jams his rifle into my belly while shouting obscenities. He pushes me across the porch, down the steps and keeps going until he has me backed into the rear fender of our car. All the while he keeps up a rapid stream of threats and obscenities. I think I can probably take the rifle away from him – then I realize his wife or brother might be behind the door with a double barrel 12 gauge and that lots of us might die if I try to get the rifle.

The old man seems almost hysterically afraid. In between his threats he keeps mentioning his relatives in law enforcement, that they would take care of us. Every time I can get a word in I claim we aren’t civil rights workers, we are construction workers on the way to a job. Finally, he calms down a little bit and seems to be considering my claim that we are not “communist agitators here to destroy the Mississippi way of life.” I get the cigarette from behind my ear and speak.

“You got a light? I’m dying for a smoke.”

Idiot! I think, what a choice of words – but he stops and just looks at me for a second, with neither of us moving or talking for the first time since he jumped through the door. Then he puts the rifle down, gets a pack of matches out of his pocket, lights my cigarette – and then snatches the rifle back up, jams it into my belly and once again screams obscenities and threats.

When he runs out of breath and pauses for a split second, George, at 17 the youngest of us, leans his head out the nearest window and says.

“I’m thirsty. Can I have a drink of water?”

Our assailant stands there for a second and then he sags – his shoulders droop, he lowers the gun from my belly and turns away. He shifts his grip to the barrel near the muzzle, motions us to follow him, and lets the butt of the rifle drag in the ground as he walks past the café, around the side and to the back. There he points to a faucet on the side of the foundation and says.

“You can use that.” Without another word or a backward glance he goes up on the back porch and into the house.

We calmly fill the radiator and drive off down the road, everybody quiet and solemn. A few minutes later the reaction sets in and my hands start to shake so badly I have to stop the car. We sit there for some time, all of us talking at once and laughing and nobody paying the least attention to what anyone else is saying. When we finally calm down we go back to Biloxi and call it a day even though we hadn’t accomplished anything — except we hadn’t gotten killed.

o o o o o o o

Toward the end of 1964 we decide to tackle some of the segregated restaurants in Biloxi. One of our first targets is a little truck stop just off the main highway that runs along the coast. Four of us go in and sit down at a table in the middle of the place. It’s almost lunch time and the place is pretty busy. We sit there a few minutes and a large man comes in and walks past our table, on the opposite side from me. As he passes us, he spits on the young black man sitting opposite me. My brain doesn’t operate at all, I just stand up and snap his picture. As I lower the camera, an impossibly long arm reaches all the way across the table and snatches the camera out of my hands. I belatedly realize that the camera is attached to a very stout cord encircling my neck – and that the man pulling on the camera is HUGE. I frantically push the cord over my head, relinquishing all control of the camera to the other guy. He opens the camera, pulls the film out to fully expose it and then hands the camera back to me. While he does this, he is talking. I think he is telling me how he feels about outside agitators and race traitors but it’s really not registering on me. I stand there, paralyzed, while all this is going on. The big guy leaves and I start breathing again and sit back down. After a few more minutes sitting there, we decide enough is enough and leave. We don’t go back, not ever.

A few days later we select a segregated restaurant that we think might be more susceptible to pressure. After we sit there for a while, refusing to leave until they serve us, the owner calls the cops and they arrest two of our guys on charges of disturbing the peace. Two days later, when their case comes to trial, the courtroom is packed with several hundred local blacks. I am a witness for the defense. Apparently the prosecutor doesn’t like my answers to his questions, because he stops questioning me and just paces up and down for a while. Then he suddenly stops, shoves his finger in my face and almost shouts at me.

“What color are you, anyway, boy?”

I sit there for a minute without answering, thinking. I look at the courtroom, packed with hundreds of black people and at the officials who are all white and I think to myself, I’m going to get this SOB. Finally, I say.

‘White. . .To the best of my knowledge.”

The courtroom erupts in cheers and clapping and the judge bangs his gavel frantically and bellows “ Quiet!” over and over. In his summation, just before finding my colleagues guilty, the judge refers to “ignorant college students who don’t even know what color they are.”

o o o o o

Roger starts working with us on voter registration when he is sixteen. Somebody rats him out to the school administrators and his high school expels him. After a week or two of kicking the issue around, we finally decide to shake things up by having him apply for admission to the white high school. It seems likely that there will be immediate violence, so I call the local FBI office and request an observer when we go to see the principal. They respond that they can’t do that but that they will notify the local police. I’m afraid the local police will lead the attack on us, so I lie and tell the FBI we changed our mind, we’re not going so there is no need to contact the local police.

We get as much information as we can on the class schedule and the layout of the building. Our plan is to park near a side door that is just a few feet from the main office and to arrive right in the middle of the third class period. We expect the hallways will be empty at that time.

I drive the two of us and we park in the street. The building sits back from the street but the side door we want is right there facing us. A sidewalk leads from the street up to a couple of steps, a small porch, and then the door.

Damn! I know as soon as I open the door that we are in trouble. The hall is full of people. Instead of getting there in the middle of third period, we hit it while the kids were changing classes.

I look over my shoulder at Roger, wondering, do we continue or do we get out of here. Roger looks frightened but also determined and nods ‘yes’. I step into the crowded hallway with Roger close behind. I keep expecting some reaction from the students, maybe even an attack, but nothing happens. As far as I can tell, nobody reacted to us at all.

Thank God, the office is only a few feet down the hall and there are only a couple of students in it. We go up to the counter and after a minute the secretary looks up and immediately focuses on Roger.

“What do you want?”

Roger replies “I’d like to see the principal, please.”

“What for? You don’t belong here.”

“Yes, Ma’am. But I want to apply for admission.”

“You can’t go here. Colored go to the other school.” Pointing to me, she asks “And who is he? What’s he doing here?”

I say “Just a friend. I drove him here.” What I’m thinking is that we aren’t even going to get past this guardian of the ‘Mississippi way of life’.

“Hmph! A Yankee.”

Roger speaks again, “May I see the principal.”

I think she is about to call the cops or maybe the Klan, but she finally announces that Roger can see the principal but that I have to wait out here and she points to a chair for me.

The hallway is empty, everybody is back in class – we don’t seem to be in any immediate danger. I have nothing to do except obsess about our situation – I know that if there is violence, it will be directed mainly at me because I am the outside agitator and as a white am by definition a ‘race traitor’. The wall clock says only a few minutes have passed but it seems forever to me. When Roger finally comes out of the principal’s office, I stand up and we head for the exit without a word.

Roger steps through the exit door and pauses at the edge of the porch. I am right behind him and my peripheral vision catches movement on both sides of the door. Two large men are standing there, one on either side, pressed up against the wall. And both of them are swinging at my head! Reflexes take over and I duck. The guy on my left swings so hard he almost falls down and ends up in front of me, teetering on the edge of the porch.

I think ‘just a little push and he’ll fall down’ and I reach out to push him in the middle of his back. Even as I reach for him, I realize this will escalate the situation and I yank my hand back just before touching him.

By this time Roger is on the path, courageously waiting for me, and, as I step off the porch, he starts to run. I know that running will encourage the two guys – I lunge forward and manage to snag Rogers shirt-tail and, I bark one word.

“Walk!”

We walk.

The guys come after us, one on either side, screaming and hollering, but keeping a little distance to either side.

We keep walking.

The thugs continue screaming and hollering and keep pace with us, but they also get further and further out to the side. By the time we are halfway to the street, I am sure they aren’t going to do anything – unless we screw up and encourage them somehow.

We finally get to the street and the thugs just stop and stand there while we get in my car and drive away.

Roger comes to the office the following afternoon with a big grin plastered all over his face.

“I got a call from my school. They reviewed my situation and decided I should be re-admitted.”

o o o o o o o

Martin Luther King was part way through the march from Selma to Montgomery when we in Biloxi decided to have a march of our own. Biloxi had previously had several civil rights demonstrations and they had always ended in violence against the peaceful demonstrators, so there was a lot of fear on everyone’s part. But we wanted to do something to honor the clergymen who had recently been killed in Alabama.

The march was to start at a church on the far side of the black part of town, come down the main commercial drag for the black community, cross the railroad tracks into the white part of town and continue for several blocks to the federal building. The route passed more than a dozen black businesses – three nice bars, several restaurants, a hotel, two movie houses, convenience stores, beauty parlors, and several real dives. There would be perhaps 70 people in these businesses on the Sunday afternoon as the march went by. We arranged for every one of these businesses to close a few minutes before the march got to them. Many of the patrons from these businesses joined us as we went past. Despite the widespread belief that we would be violently attacked, about 200 of us marched to the federal building.

A little old lady who we all call Grandmother comes down from Jackson as our featured speaker. Grandmother is less than five feet tall and several feet wide. But she has a tremendous air of authority and calm about her.

Grandmother and I walk, with her arm linked in mine and 200 people following us, through the black business district, across the railroad tracks into the “nice” part of town, and to the federal building. I hold her arm while she climbs the stairs and I wait until all of our demonstrators are gathered on the pavement below us. I say a few words of introduction and she begins to speak.

Grandmother is barely started on her speech when the first young white men show up on the other side of the square. I notice right away that they are drinking and carrying rocks and clubs. Grandmother is facing them, she has to see them. But she gives no indication of noticing them, just keeps on with her speech.

The square behind us is rapidly filling up and pretty soon there are two or three times as many white men waiting for us as there are people in the march. And many of our people are old or women – or both!

I keep looking for the Chief of Police but see no sign of him nor of any cops. I know by this time that the Chief of Police is a reasonable man and that he is doing his best to avoid any serious trouble – Biloxi, after all, is a tourist town and violence is bad for business. I called him several days previously and explained our plans to him, in detail. I expect him to show up.

I finally give up looking for help from the cops and concentrate on trying to keep my fear at bay. I’m the only white in the demonstration and will be the target of many of the attackers. I expect to die. And Grandmother is still talking. Many of our people are frightened and spending their time looking at the mob across the square. It is all I can do to restrain myself from running up to Grandmother and begging her to leave, NOW!

Finally! Grandmother stops talking, climbs slowly down the steps and comes over to where I am standing. She takes me by the arm and starts walking straight at the center of the mob. After a few steps, still walking, she looks over her shoulder and says, “Sing loud and walk slow”, and she begins “We shall overcome”.

We head for the center of the mob. I am going to die in just a few seconds, but Grandmother’s arm is supporting me, lending me courage and I keep walking and even manage to sing a little. Sweet mother of God, the crowd parts as we get near it and Grandmother and I are now between the two arms of the mob as it continues to open before us. Just then we get to the part of the song that says “Black and white together” and I cringe, sure that this will incite the attack.

Nothing happens. We keep walking and singing.

After an eternity Grandmother and I are through the mob and then we’re at the railroad tracks and I’m still alive and now we’re safe.

When we debrief, we find out that the Chief of Police and at least several of his men were in the mob, all of them in plain clothes. None of them were in the front row, rather they were in the second or third rows, scattered around and waiting for the right moment. When Grandmother and I got close, when the mob mentality was waiting to see who would make the first move, the Chief and his men moved back, they stepped away from us. The mob followed their lead and parted for us.

o o o o o o o

That evening after our demonstration I get a phone call from home. My precocious seventeen year old sister Pamela and several others from her college are on their way to Montgomery Alabama to help in the demonstrations that have been going on while King and his march approach the city. All the excitement and all the national media have been focused on Selma and Montgomery for weeks. We have been resisting the urge to run over there and be part of it, but this is too much. Several of our people have met Pamela and my parents and we can resist no longer. We go to Montgomery.

Montgomery is a madhouse. There are civil rights workers everywhere and more arriving all the time with no central records anywhere and a vast square filled with what seems to be thousands of people. I despair of finding Pamela. I spend 30 minutes sitting in the top of a tree with the thought Pamela will see me if she is out there, but nothing.

People are sleeping everywhere. The churches are full, people sleeping on all available floor spaces. Private houses are full. The air is full of hope – nothing can resist this many committed people.

Our first morning in Montgomery, I’m up early, sitting on the church steps, wondering what excitement we will have today, and James Foreman, the head of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality), comes out with a broom and begins sweeping the street that is covered with trash from all the people. I watch for a few minutes and several other people join him, all sweeping. I go over and take the broom from Foreman and tell him that we will finish the job. This becomes a morning ritual – I wait for Foreman to start sweeping and then I take the broom from him and we finish while he goes and plans our day.

One morning we form up as a march and head for the nearest black high school. We don’t ask permission, we just go in and march through the building, singing and urging the kids to join us. The kids are ecstatic, screaming and jumping up and down with excitement – they want to join the march, they are afraid to join the march – afraid of what their parents will do to them, afraid of the Klan, afraid of jail. Many of them eventually run to join us and we go on to another black high school where the routine is repeated. Eventually the whole mass of us, many hundreds strong now, head for the capitol.

Halfway there we run into a police blockade and the march stops. It’s a hot day and Bill Ware, another civil rights veteran, and I decide to go search for water. We’re in a residential neighborhood and on foot we can’t find anything so we head back. As we get close, we find mayhem. Right after we left, men on horseback armed with clubs rode into the mass of demonstrators, clubbing all they could reach. Many people are hurt. I carry an injured young woman into the hotel, headed for the impromptu first aid station on the third floor. The elevator doesn’t come and doesn’t come and I finally carry her up the stairs.

People are in shock, angry, frightened. Everybody gathers around the church headquarters and one of King’s lieutenants, Rev. James Bevel, starts to talk to the crowd from the church steps. He is trying to deal with the trauma people are feeling and it’s helping, but many of us are keeping our eyes on the cops who are massed at both ends of the block, completely blocking the street on both ends.

As Rev. Bevel talks, a cop on a big Harley comes roaring down the street and people jump out of his way as he shoots past. This is too much for me. I am angry, but it is an icy cold rage and I am completely calm. I look around for some other veterans, but all I can see are new people who mostly seem on the verge of hysteria. Where the hell is Bill Ware? He would be able to help. Finally I give up searching for any help and move to the edge of the crowd. Ah! There’s Bill, sitting down on the edge of the crowd, right in the path of the motorcycle which is turning around and, after a slight pause, coming our way again. I kneel in the street next to Bill and now I’m the one sticking out past the edge of the crowd. The cop comes at me and at the last minute swerves to miss me. Somehow I knew he would.He goes all the way to the end of the block and this time doesn’t pause but turns and immediately comes back. I have turned to face him and am still on my knees. Bill is sitting on my right and beyond him the crowd is dense. The sidewalk, to my left is perhaps six feet away. If we can get that six feet filled with people, we will have the street. The cop accelerates at me and this time I think he won’t swerve.

Just before the cop gets to me time slows down or my body goes into overdrive. I don’t understand it but, in spite of a cop on a big Harley speeding right at me, I have everything under control. At the last instant I turn slightly so the bike doesn’t hit me head on. I am squatting, knees bent, and somehow the bike is sliding past my back and hips and I push, hard, with my legs and I end up on my feet, facing away from the bike.

I look over my shoulder and see that the bike almost goes over and slides completely around until it is facing back at me. The people who had been cowering on the sidewalk are now enraged, they think the bike ran over me, and they move quickly toward the motorcycle cop, shouting and waving their fists as they go. All I can think about is the cops massed on either end of the block and I need to calm this mob in a hurry or the cops will start shooting. I raise my hands to the mob and I feel ridiculous and this picture of Moses spreading his arms over the Red Sea pops into my head – but the mob comes up to me and stops and nobody is attacking the crazed motorcycle cop and we have the street.

o o o o o o o

Later I discover my sister Pamela is a hero and successfully defied the men on horseback. The next few paragraphs tell her story in her own words.

I was in the front of the line when the men on horses arrived. I wasn’t afraid of their clubs and decided to stay put. Then I noticed the ropes and I was afraid of being dragged. Even as I was thinking it I knew it was irrational to fear the ropes and not the clubs – but I turned and started walking up the street. In just the few seconds it took to have these thoughts, the street that only seconds earlier was full of hundreds of people, now was mostly deserted.

I had only gone a few steps when I saw that five or six people were pinned up against the side of a house by three men on horses. The house was on one side, big thick tall bushes on two sides and these men on horses pushing them tight against the house, and swinging their Billy clubs at heads and upraised arms. I got so mad that I forgot to be scared and walked over toward the horses, yelling.

“What do you think you’re doing? Stop That! Why are you hitting those people?”

I just kept yelling and walking till I was right next to the horses and one of the horsemen actually answered me.

“These people won’t move down the street, they need to move on.”

So I answered, “How do you expect them to move, there is no place to go. Move your horses back and they will go up the street.”

Most amazing, they all stopped swinging their Billy clubs and moved their horses back and the people did start going up the street. Then one of the horsemen told me to start walking and he put his horse behind me and started pushing me with the horses’ shoulder. I was still too mad to be scarred so I went as slow as I could and asked him.

“What will you tell your grandchildren about this day?”

Eventually he stopped pushing me and I saw a young white man all alone lying on the grass. He was not moving and I didn’t know if he was dead or alive so now I was really mad. I went over and he had been smashed in the head and there was blood running down his face into his eyes. He was dazed but not unconscious so I helped him get up and someone got in my face with a camera and I told him to take a picture of the kid to show what was done here today. The photographer was Charles Moore and those photos made it into Life Magazine and Photography Annual. After I held the kid up for a few minutes he said he was Ok and can find his friends. I never even found out his name!

o o o o o o o

The next day Foreman and the other honchos decide to change tactics. A handpicked group of 100 will march on the capital. Bill Ware and I are picked as the marshals to lead them.

We set off about mid-morning and head directly for the capital building. We reach the square in front of the capital building and, dead center in front of the capital, we take our positions on the wide sidewalk. Bill and I are stationary, about 70 feet apart and the rest of our people are marching in a flattened oval around us. I have plenty of time to look around.

There is a solid line of state police between us and the capital. Our group is marching around and around just in front of the building, and in the street next to us are about a dozen city cops. Off to the left there is a large crowd of white folks, but many of them seem to be media types – I can see several TV cameras and I don’t hear any threats or obscenities. I don’t think they pose any danger.

For about fifteen minutes we march around and around, Bill and I still providing the anchors. Mostly the cops just watch although a few can’t resist taunting us. Then, a large noisy, angry mob comes into the other end of the square. I can see the clubs, even though they are at least a city block away. The cops are gleeful and tell us it’s the White Citizens Council and we are now dead meat.

I feel the hatred as a tangible force and it is frightening. One young couple panics and leaves despite our efforts to convince them it is more dangerous if they are by themselves. Finally, seeing they are totally freaked, we tell them to head for the TV cameras off to the left. They leave and I never find out what happens to them, whether they made it or were beaten or what.

The mob is gradually getting closer and our oval is collapsing on that side. Our people are coming around me and then shrinking further and further away from the mob until I am afraid our march will collapse into chaos. I step outside of our oval with my back to the mob and, as people make the turn, I tell them to keep a nice straight line and point to show them what I mean . The mob is getting louder and louder but our line straightens up and I figure we will keep a nice line up to the instant they start clubbing us.

Our people keep marching and I am still telling them to keep a straight line. The mob is getting louder and louder and I figure they must be right behind me. I have this terrible desire to look and see how close they are but I will be damned if they will see how scared I am and I don’t look behind me.

All of a sudden the city cops move in and begin arresting us. I look around and the mob is gone and I am really confused – what happened to all those angry men? How could they have disappeared so quickly? I am so tense and frightened I don’t go limp and two of the cops easily easily lift me into a paddy wagon. When I don’t move to the back, a cop says to me.

“Wanta keep your nuts, you’ll move back. TV cameras can’t see in here.”

To my shame, I practically leap into the back.

We’re put in big holding cells, whites in one and blacks in another. Jail is really boring and I am in with a bunch of strangers who are brand new to the movement. Finally it is time for dinner and all of us, black and white, go to dinner together. To get to dinner, we come out of our cell, walk toward the cell where the black guys are coming out, and all of us turn and go down a very long corridor to the dining room. One guard stands in front of each cell, two more together where we turn into the long corridor and another at the entrance to the dining room. I notice they don’t look at us as we go by – they seem barely awake and bored.

All of us are on a hunger strike, so we don’t eat, we just turn our plates upside down and leave the food. On the way back from dinner, going down that long corridor I watch as the guys ahead of me make the turn – whites to the left, blacks to the right. When I get to the turn, I go the wrong way, with the blacks. The guards don’t notice and I have integrated the jail. Of course, later the guards do a roll call and I am caught and put back in the “right” cell.

o o o o o o o

The next day my second day in jail, the whites are taken to breakfast first and then the blacks go after the whites finish. Instead of eating, we turn our full plates upside down and sing until they take us back to our cells.

At lunch we go through the ritual of turning our plates upside down and leaving all the food. Since no one is eating we are quickly on the way back to our holding cell. Halfway down the long corridor there is an alcove with a shower in it and I step into it and wait while the black guys go to eat. I sit in the shower until the black guys are on the way back to their cell. I listen carefully because I don’t want to risk sticking my head out to look down the corridor and I sure don’t want to suddenly appear until the corridor is full of people. When there is lots of noise and I think the corridor is full, I boldly step out into plain view of the guards at both ends of the hallway. Damn! There is only one other prisoner in this entire immense hallway and all the guards are looking right at me.

There isn’t anything else to do so I keep strolling down the hall. Somehow the guards haven’t noticed that I just appeared out of thin air and a minute later I have integrated the jail for the second time.

More demonstrators are being arrested all the time and the jail is filling up. At evening roll call, I somehow manage to fake my way through it and they don’t catch me. Instead they take the whole bunch of us out and load us into paddy wagons for transfer to a state facility on the outskirts of town. The paddy wagon starts to pull out of the yard and I am just congratulating myself on how clever I am when I hear shouts, followed a moment later by someone banging on the door and the paddy wagon abruptly stops. The doors fly open, two cops come in looking carefully at people and I am caught.

They don’t take me back to the white holding cell. They take me far away to the back of the jail and put me in a room by myself, a room half full of old desks, and leave me. I look around and I can’t see anybody else. I can’t even hear anybody else. And these desks and the floor are covered in a thick layer of dust. It suddenly hits me. I am totally isolated, in a room that hasn’t been used in years and the only reason I can think of is that they intend to kill me. Shit! Now I am really scared. Maybe they will only beat me. I’ve never really been seriously beaten and the prospect scares me badly. I’m on the verge of panic, trying to hold it together. This goes on for quite a while and I can’t think of anything to reassure myself.

Eventually a little old man with white hair comes along, unlocks the door and comes in with me. We stand there for a while just looking at each other. I can’t see his gun or any other weapon but he must have them. I’m a little surprised that my executioner is a little old guy with white hair, but mostly I’m just trying not to let on how scared I am. Finally he speaks.

“Why are you causing so much trouble?”

His tone of voice is plaintive and I realize he actually wants to know. Thank God Thank God Thank God, they’re not going to kill me. I am so relieved I can’t even speak. I just continue to stand there staring at him. I know I should answer him, but I can’t. My relief is so immense there is no room for talking. Finally he gives up waiting for me to speak, shakes his head ruefully and goes away. A minute later a guard comes for me and escorts me to solitary confinement.

This really sucks. The room is tiny and the bright lights stay on all day and all night and I can’t even sleep well. Three times a day a little slot opens and a plate of mush appears. I push the mush back through the slot, uneaten. I discover a little hole in the back of the room, up near the ceiling and by standing on the bed and stretching up I can look through it and see more demonstrators being ushered into the jail several times a day. By the second day I feel like I have been here for months and the only thing that keeps my spirits up a little is the steady stream of arrested demonstrators coming into the jail. It’s hard to keep fasting when you don’t know what everybody else is doing. That evening I eat the mush instead of pushing it back through the slot.

After three days in solitary I am beginning to feel like my brain and body are both atrophied. Without warning, they come for me and, along with about seventy others, I am transferred to the big state facility on the outskirts of town. Blacks and whites are all mixed up together for the trip and it is heavenly to be with colleagues again. By the time we get to the state facility I am ready to conquer the world again.

I integrate this jail by simply strolling into the wrong holding cell and the guards don’t’ seem to care. I lose track of the days, but think the total for the two jails is eight or nine days. I check the date and realize it’s time, I have to go back to Penn State.

I feel guilty about making bail while the jail is still full of demonstrators. But the arrangements are all made to return to Penn State for the spring term and to run for president of the student body. It was already the last minute – I either get out of jail now or a lot of people will have wasted a lot of work.

2007 – 43 Years Later: Personal

Forty three years later the incidents described above are still vivid and fresh in my memory, burned into my brain and soul and I doubt they will ever fade. Mississippi Freedom Summer was a transformative experience, we were never the same afterwards.

I first saw Fannie Lou Hamer during the training when her rendition of “Let Your Little Light Shine” brought tears to our eyes. Fannie Lou had little education, her job experience consisted of picking cotton, and she lived in housing owned by the plantation where she worked. In that impossible situation, Fannie Lou decided she was tired of being afraid and set out to register to vote. She persisted in trying to register to vote and she was arrested, she was severely beaten, she was fired, and she was thrown out of her house. Her response? “Free at last, thank God, I’m free at last!” and she went to work full-time as a civil rights activist.

Steptoe was about five feet six inches tall and so skinny he looked like he was made out of rawhide. He was a farmer and had title to his land so he couldn’t be fired nor thrown out of his house. The Klan, once or twice a month, drove past his house and shot at it as they went by. Steptoe simply kept on trying to register to vote and continued working with the civil rights project. He had stopped being afraid and there was nothing the Klan could do about it.

One of the tactics that SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) used was to follow a racist sheriff around and imitate his swaggering walk. While exceedingly dangerous, the black community found this hilariously funny and it helped dispel the fear that these officials cultivated and depended upon in keeping the black community docile.

Fannie Lou and Steptoe and all the other incredibly courageous black Mississippi folks demonstrated that freedom is a state of mind that has little to do with external circumstances. Once you get that understanding thoroughly beaten into your head, there isn’t anything that anybody can force you to do. You know, deep down in your soul, that whatever you do is your choice. Even with a gun to your head, you always have the freedom to say no to the oppressor. And that understanding robs the oppressor of most of his power.

2007 – 43 Years Later: Sociological

The individual incidents are still fresh in my memory, but it is hard to recall the system of segregation. Memory fails and imagination balks to recall a system of such evil.

This system was essentially unchallenged in the hundred years after the Civil War. In the early sixties, SNCC challenged it by sending field workers into the deep South. They were pretty much continutally beaten, shot at, arrested, and harassed by both government officials and the Klan. By the end of 1963 these brave souls were emotionally and physically exhausted and near collapse. And the outside world was essentially ignoring what was happening to them.

The Mississippi Freedom Summer was a brilliant response to this dire situation. The national news media ignored what had been happening to local blacks in Mississippi. When I went to Mississippi, I had professional parents who knew how to work the media. I had parents who could call up a congressman or a senator or the US Justice Department and demand that the laws be enforced properly. And the media attention I got back in Pennsylvania outraged a lot of other people beyond just my family and friends. And there were a thousand others just like me. Suddenly there was a constituency all over the nation for doing something about this scourge of segregation.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but when the Klan murdered Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman, right there they lost the war. In a sense, the entire next year – all the work we did in Mississippi, King’s march from Selma to Montgomery, and all the rest, was just mopping up, just a way of keeping the evils of segregation in the news. The Klan’s reign of terror was over – people stopped being afraid of the Klan and they had no other power. In 1965 the first serious civil rights law was passed and blacks could no longer be denied the vote. Mississippi’s “way of life” had been irrevocably destroyed.

The first law of fighting evil is that it can’t stand the light. Even the Nazis went to extreme lengths to hide and disguise what they were doing to the Jews. When you shine the spotlight of publicity on evil it generally shrivels and dies.

Mississippi changed because two critical things happened: local blacks in large numbers decided to be free and the evils of segregation were caught in a glare of publicity so bright that none could deny it. As a result, Jim Crow shriveled up and died.